The Great Famine

The 2015 Annual Famine Commemoration will take place on Saturday, 26th September, in Newry. This is the eighth year in which the Great Famine has been marked with a formal Commemoration and the first time that the Commemoration will take place in Northern Ireland. In recognition of the fact that the Great Famine affected all parts of the island, the location of the annual Commemoration has rotated in sequence between the four provinces since the first Commemoration took place in Dublin in 2008 and falls to Ulster in 2015.

The Great Famine was one of the bleakest periods in Irish history and one that, it can be argued, altered Irish life irrevocably; everything from economics, politics and culture was changed completely.

In the 1841 census, the population of Ireland was approximately 8.2 million people, but by 1851, this had decreased to 6.6 million. 1.1 million people died either of starvation or due to illnesses associated with hunger, such as typhus, dysentery, scurvy and small pox. Well over one million emigrated to England and North America. This brief article will explore why the Great Famine was so devastating.

Economic background

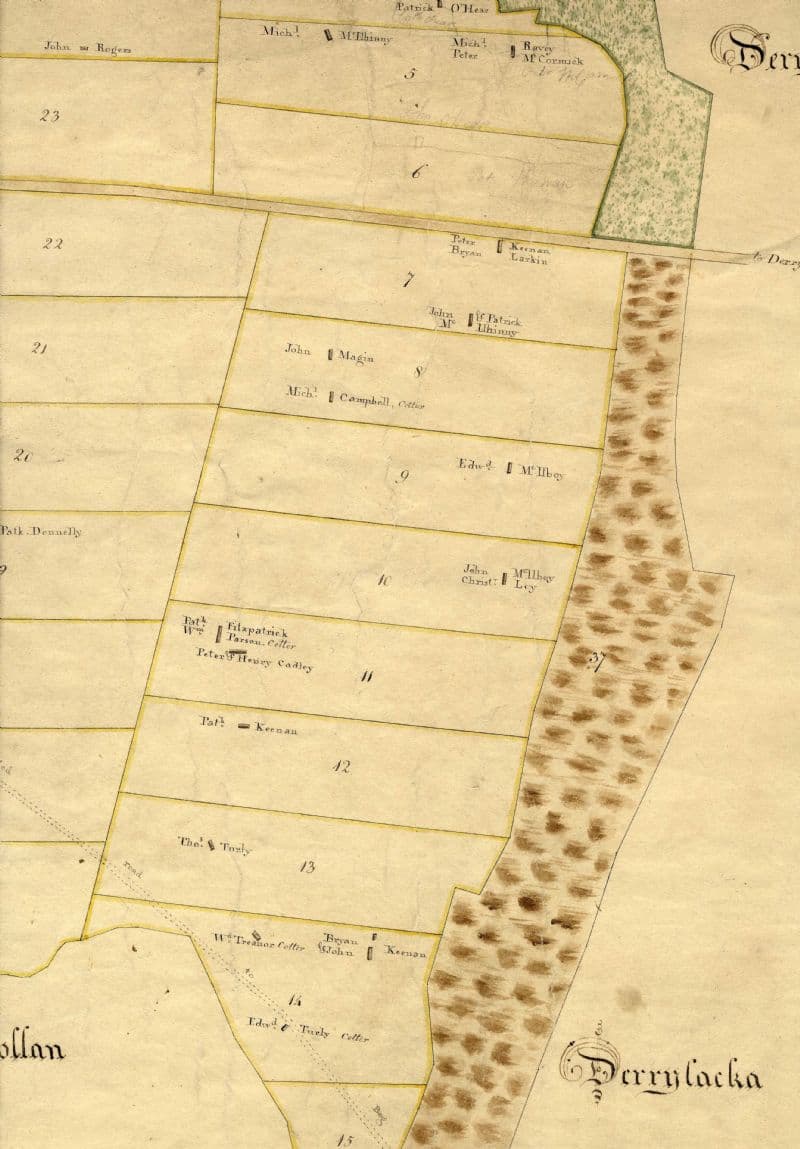

In the 18th century Ireland was pre-dominantly an agricultural nation, concentrating on pastoral (cattle, chickens and sheep) rather than arable farming(growing crops). The basic structure of landownership was a hierarchy, with landlords at the top, tenant farmers in the middle, and at the bottom were agricultural labourers or cottiers who received small plots of land from the tenant farmers in exchange for their labour.

Market forces between 1780 and 1830 diverted agriculture into cereal production, such as wheat and oats. A growth in the English population and the Napoleonic Wars increased the demand for these crops. This high demand and rising food prices boosted prices and profits for Irish farmers and landowners and saw Ireland becoming Britain’s ‘bread basket’. This demand led to an increase in labourers or cottiers who were given land in return for labour, providing landlords with a cheap labour supply. Potatoes became the principal food on which the cottier depended with adult males consuming between 10 and 15 pounds daily.

With the ending of the Napoleonic Wars prices fell affecting cottiers most as farmers no longer required a large workforce to produce crops that were cheaper to import. The economy began to stagnate and was vital as there was no other means of employment. There was an even higher reliance on the potato as there was an absence of alterative employment opportunities. In these circumstances a failure of the potato crop could be disastrous.

Potato blight

In September 1845, a fungal disease, Phyophthora infestans that had spread throughout the greater part of northern and central Europe reached Ireland. “Leaves on potato plants suddenly turned black and curled, then rotted” and approximately one third of Irish potato crops failed that year. Ireland had experienced famine and crop failures before but this was a new disease for which there was no cure. It struck again with more force in 1846.

With the almost total failure of the crop in 1846 and a bleak winter in 1847, millions faced starvation. The potato provided a healthy diet and, once this source of nourishment was removed, those who did not die of hunger died of sickness and disease. Relief measures were implemented by private organisations such as the Society of Friends who provided food and clothing, seeds and money. Soup kitchens were set up in towns and rural districts.

Government response

The government in 1845, under Robert Peel responded by purchasing Indian meal from America which those starving could buy by earning a small wage through a programme of public works that involved the building of walls, roads, bridges and fences. This was regarded as a prompt and relatively successful action.

The situation changed, however, under the new Whig government, led by Lord John Russell, which came to power in 1846. Their economic policy was based on the doctrine of laissez-faire, which meant that the government did not intervene in the internal market or in the export of agricultural produce.

It has been argued by many that there was sufficient food in Ireland to feed the hungry and prevent starvation. Writers of the time such as John Mitchel had strong views, arguing that there was a deliberate policy to clear Ireland’s ‘surplus population’. Historians and commentators in modern times have also been critical of the British government’s response.

Workhouses

The ‘Gregory Clause’, which was part of the Poor Relief Act of 1847, stated that any family holding more than a quarter of an acre could not be granted relief. This made it easier for landlords to clear their land for pastoral production and evictions of tenants increased. Many had no option but to enter the workhouse.

The workhouse system had been introduced to Ireland under the Poor Law Act 1838. Around 130 workhouses were built in Ireland, 43 in Ulster alone. They were seen as the refuge of last resort as families were divided with men, women and children over two years of age assigned to different wards. Food was limited and discipline was strict. Inmates were required to work at breaking stones or tending to the sick. During the Famine they were overcrowded and sickness was rife due to very poor conditions such as damp beds and poor sanitation.

Emigration

For those who could afford to, emigration was another way to escape hunger. Thousands left Ireland for Britain, North America and Australia. There had been a steady flow of emigration from around 1815 but this increased and emigrants from this area left Warrenpoint for St John’s, New Brunswick in Canada, New York, or Liverpool. Known as ‘coffin ships’, emigrant ships were often overcrowded, inadequately provided with food or clean water and became synonymous with sickness and disease. Many emigrants died on the voyage.

Consequences

If the food shortage had been limited to 1845, mass starvation could have been averted as Ireland had suffered crop failures and famine several times before, as well 1845, there was a total failure in 1846 and failures in 1848 and again in 1849.The government’s response to the worsening conditions by refusing to adequately finance, empower and organise relief certainly after 1846 had calamitous results. The public works and workhouse systems were under tremendous strain as they could not cater for the rise in numbers seeking relief.

The Famine and the infestation eventually began to show signs of waning in 1850 - 1, but by then at least a million people had died from either starvation or disease associated with malnourishment. Mass evictions saw families forced from their holdings. In the eleven years during and after the Famine Ireland sent abroad over 2 million people, more than had emigrated over the preceding two and half centuries.

Legacy

The Famine would leave Ireland changed unrecognisably. It would leave a lasting legacy of mistrust between Britain and Ireland. The cottier class and the landless labourers were decimated altering the social structure of Irish society with the ‘strong farmer’ and tenant families now the dominant social group. It would leave a legacy of continuous emigration and accelerate the decline of the Irish language. Some would say the effects are still manifest today.

Over the coming weeks Newry and Mourne Museum will produce a number of articles looking in more detail at the effects of the famine on the Newry and Mourne area. Articles will include, the workhouse, effects of famine in South Armagh, and local encumbered estates.

Newry and Mourne Museum will host a wide range of events for schools and for all those who are interested in learning more about this period in Irish history, one that altered Irish life completely; everything from economics, politics and culture was changed.

These events form part of an extensive programme of activities organised by Newry, Mourne and Down District Council for the 2015 Annual Famine Commemoration taking place 26th September in Newry.